The system has been broken for generations.

When my UNH professor walked into Elementary Arabic last Monday, I could immediately tell something was off.

Instead of cheerily announcing “Assalamu alaikum ya shabab” to his tired class of seven, he entered the room quietly and connected his laptop to the projector. In a matter of seconds, the screen flashed to display UNH’s Academic Integrity policy, which, without hesitation, my professor began to read aloud.

“Plagiarism: The use or submission of intellectual property, ideas, evidence produced by another person, including computer generated text, in whole or in part as one’s own academic assessment…”

As he finished, I noticed the eyes of my classmates shifting around the room, nervously looking at the homework they hastily scribbled down before class. With frustration in his voice, my professor began to speak, then paused, as if he couldn’t believe what he was about to say next.

He told us that as he was grading our one-page reflections on Muhammed: Legacy of a Prophet—a film in which American Muslims tell the story of the Messenger God—an AI writing detector identified that two out of seven papers had been written using ChatGPT.

“I need you to know that when I saw that, I was so sad” he told us, placing both hands over his heart. He then indirectly spoke to the students who had used ChatGPT, asking them not only why they were taking this course, but why they were attending university in the first place. He said he couldn’t comprehend why someone would pay $50,000 a year to become a good cheater instead of an educated human being.

Strangely enough, although I was not one of the students who used AI to generate their papers, it’s possible my professor’s remarks resonated with me most. For weeks, I had been investigating how students and teachers at Oyster River High School (ORHS) were adapting to the ways ChatGPT changed how they think about education.

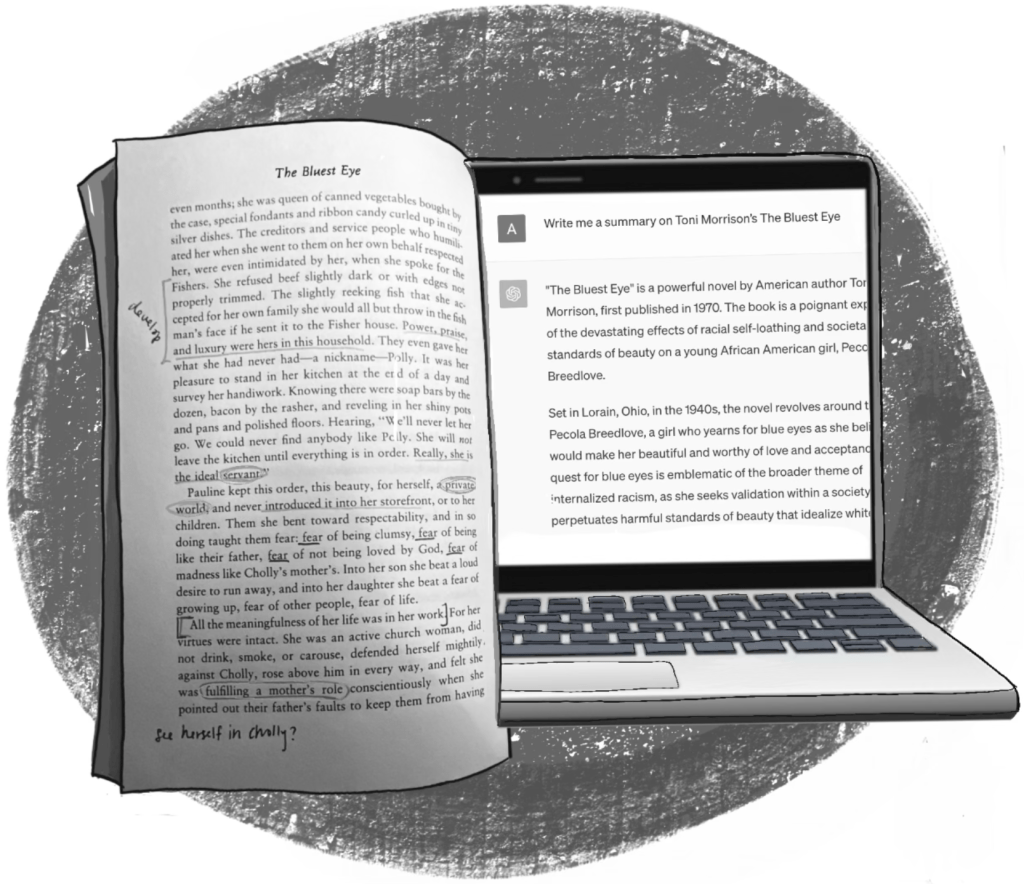

So, when my professor announced that college students were using ChatGPT to get by in a class they chose out of interest, I realized that passing off generated text as original work extends beyond my little high school bubble. That this issue is deeper than students who don’t care about Of Mice and Men or a few STEM kids who generate an essay, because they think close reading will be irrelevant to their future success. It’s possible that’s where it starts: some students don’t want to “waste time” writing assignments for classes they don’t care about.

But, according to Forbes, 43% of U.S. college students admitted they used ChatGPT to complete assignments for their major, with over 20% believing generative AI didn’t qualify as cheating. If young adults are using ChatGPT in classes designed to prepare them for their future, simply “not caring” can’t be where it ends.

So, how did we get here? When did academic shortcuts somehow become more valuable than the process of learning itself? And most importantly, what will happen to my generation, and the ones that follow it, if we grow up in a world that values the efficiency of ChatGPT more than the process of thinking and communicating original, critical thought?

II.

When ChatGPT was released for public use in November of 2022, it was never intended to pervade the education system the way it did. However, about a week after one of my friends showed me the program, I suddenly noticed more and more students using it to workshop essays, draft resumés, and even complete lab reports.

“I think now, you can ask any person in this school, and they won’t be able to tell you they don’t know at least two or three kids who have used ChatGPT to do their work for them,” said E (‘24), who was hunched over her desk, frantically copying down a ChatGPT summary and analysis of a book she was discussing next period.

Intrigued by E’s comment, I wanted to know how kids at ORHS were using ChatGPT and whether, almost a year after the program’s initial release, students had begun to think about their learning differently.

When senior S (‘24) first found out about ChatGPT from his Spanish classmates, he vowed never to use it.

However, that changed when, under a time crunch, he used ChatGPT to generate a lab report, and ended up getting a better grade than his friend, who spent the weekend researching and writing

“Now, I use ChatGPT for pretty much every type of assignment you can think of. If I don’t feel like the stuff my teacher’s assigning me brings me any value, it’s getting plugged in,” S told me.

What S told me brought me back to the explanation E gave me when I naively asked why she copied down notes from ChatGPT instead of taking them herself.

“You think I actually read the book?” she asked me. “It’s from the like 1800s, so it’s boring, and I can’t even understand what’s going on. ChatGPT like makes it so I’m able to read a summary and know what’s going on so I can participate in class.”

Most of my conversations with peers about why they use ChatGPT almost always funneled down to the experiences S and E described. They either weren’t interested in the assignment and didn’t want to put in the time. Or they didn’t feel confident enough in their own writing and knew they could get better results in a shorter amount if ChatGPT did the thinking for them.

Currently, the ORHS English department treats AI generated student work like any other form of plagiarism.

However, some students said they felt they used it in a way that wasn’t cheating. Instead of generating an entire essay, they used ChatGPT only to brainstorm ideas and write outlines, making it easier to fill in the rest. Or they would generate entire essays but reorganize and add in information to “make it their own.”

“Writing an essay is super hard for me so I always tell myself, ‘OK, let me get like the first paragraph from ChatGPT and see what it gives me… And then, I can use that in my own writing but like not actually take anything from it so I’m not cheating; it just kind of gets me started. It’s the prewriting I don’t want to take time to do,” said S.

Some teachers, like ORHS economics teacher Adam Lacasse, believe that because generative AI will only become more prevalent, we should teach students how to use it as a tool.

“As an educator, I use ChatGPT all the time. For me, it helps with creativity. I could create in my brain 20 different practice questions about supply and demand, or I could go to ChatGPT to have it generate those 20 questions for me. You know, I already have this knowledge; so, ChatGPT is a tool for efficiency that provides opportunities.”

Lacasse says that as long as ChatGPT isn’t getting in the way of students building foundational knowledge or replacing “independent thinking,” it should be embraced.

But, part of me wonders whether ChatGPT could ever serve a valuable purpose in education, given how fine the ethical line seems to be. I mean, what if my definition of ChatGPT inhibiting independent thinking is vastly different from my peers’? What’s the real difference between having ChatGPT write your outline and having it write your essay? What do you tell students, like senior M (‘24), who believe it’s impossible for ChatGPT to be unethical because “humans aren’t original either.”

During our conversation, M mentioned that teachers who’ve been teaching the same books for 20 years have seen recycled ideas, just written differently. “How many times have you had an original idea about a classic? I’d argue never,” he told me. “Like, since when have original ideas been a big part of education? I think it’s pretty much just regurgitation at this point.”

M continued: “I actually think the argument that ChatGPT isn’t original is dumb because it’s just doing what humans do. It’s just taking external information and recombobulating it in its brain,” said M. “Going by that logic, we don’t have original thought either. That’s just what humans do. It’s just a smart human.”

In the days following my conversation with M, I tried to grapple with what he had told me. I knew I didn’t fully agree with him, but I had trouble placing my finger on where, exactly, his logic was flawed.

So, when I met with Jake Baver, head of ORHS’ Writing Center, I asked him what he thought about what M had told me.

“I think that if we look at thought as only being valuable if it’s original, and if our assignments in school give the impression of ‘true originality,’ then those [who feel everything’s been thought] aren’t willing to break thoughts that existed before to make it original in their own sense. That’s a problem,” said Baver.

“There needs to be an understanding that the experiences that I’m having and the life that I’m living probably has been lived already in some way, shape, or form. And yet, I’m still this original product that can break off from the path,” he continued.

That’s when I realized M’s way of rationalizing using ChatGPT to bypass actual effort was not some mega-genius thinking that had gone over my head. In fact, both M and I had forgotten to consider one important thing: education is not solely about the final product; it’s about the process of getting there.

There is no way to make that sound less trite. But, then again, if most students have forgotten that the process of learning the thing—of getting excited to uncover new information through research or finding new, innovative ways to think about dusty, age-old ideas—is the reason we go to school in the first place, maybe the cliché hasn’t been drilled in enough.

In my reporting, and even during casual conversations with my peers about ChatGPT, I remember searching for kids who had a moral aversion to AI’s invasion of the education system. But I never found any.

Of course, there were students who didn’t use it, but that was because they were scared they were going to get caught or knew ChatGPT’s writing was inferior to their own. No one ever told me they feared ChatGPT would detract from their ability to learn, a response I initially thought would be the most common.

Actually, I remember prodding a student to give me the answer I was looking for, asking him what he thought the purpose of coming to school was if students were going to have ChatGPT spit out ideas for them.

“You think I come to school because I want to learn?” he asked me, letting out a laugh as if it was the most outrageous thing he’d ever heard.

I was shocked.

But, in the same vein, I also don’t know why I expected another response, when that’s how my peers and I have been indirectly taught to think about education since we started getting graded.

III.

“One of the things I worry about is the way we generally suck the joy out of education,” said ORHS English teacher Sherri Frost, who’s been teaching since 2006. “I think about little kids and how excited they are to go to school. That’s when everything’s fun and everything’s great. Then kids get to high school and all you hear is, ‘Is this going to be on the test?’ It’s all about this arbitrary grade you want to get so you can stay competitive.”

The way kids view education as some twisted competition has been obvious to me for a while but became even more clear when I sat down to meet with U (‘25), who was writing an article about why it’s valuable for high school students to engage in philosophical discussions.

As he was speaking, U kept having what I can only describe as revelations: “What if we didn’t only value grades? What if we enjoyed the feeling learning and discussing gave us more than the feeling of doing better than our peers or getting an A?” As he rhetorically asked me these questions, I wondered if it was always supposed to be this way.

In U.S. History, we learned about Horace Mann, who fathered the free compulsory education system in America in the 1850s. Sure, one of his motivations was to train and prepare America’s emerging working class for a newly industrialized society. But what we would now call “career planning” was not the backbone of American education like it is today.

Mann was mostly guided by his belief that, in a time where the country was starkly divided, a basic level of literacy and a discussion of common ideals would promote the critical thinking necessary for a healthy democracy. Thus, our education system was built to nurture good communicators not good competitors.

So, what would Mann say if he found his vision of the American education system had rotted? What would he say to the parents who struggle to find value in their child’s humanities degree, or the multi-million-dollar corporation that profits from telling students standardized test scores measure intellectual potential? What would he say to those who consider learning beyond the context of As and Fs revelatory, when that’s where the education system started?

Maybe he would find that most students don’t enjoy learning in school because, over time, learning has become synonymous with competing. Competing with your peers and also with your past academic self. Maybe he would find that generative AI was bound to seep into a system that’s already sullied by doing whatever it takes to get ahead.

This is why I’m sick of the narrative that ChatGPT has “ruined” the education system.

This system has been broken for generations. Just ask your parents. How many of them used Cliff’s Notes for English or used an essay their sibling wrote three years earlier? What ChatGPT has done is make cheating more available and efficient. In fact, its efficiency is so irresistible that even students like U, who deeply value the process of learning, have turned to it once or twice.

Now the question for educators becomes what to do next. Although some teachers can easily identify ChatGPT’s hollow writing or have AI detectors at their disposal, determining whether a student has used it is accusatory at best.

It seems the only way to fully deter students from replacing independent thought with this bullshit technology is to remind them of why they go to school in the first place. For educators, this means fostering a learning environment that is not competitive and grade oriented. It means encouraging students to think and share out of the box ideas without labeling them as “academic risks.”

Baver told me a story about a kid who came to him for help with an assignment in which the student had to analyze a quote and say how they felt about it.

“He was consistently ChatGPT-ing it, and I could tell he just didn’t get why I kept telling him to write it… Then, when he came to me the last time, I asked him how he really felt about the quotes.”

The student told Baver he thought the quotes were terrible and that they sucked. Baver told him to be honest and write that instead of the “ChatGPT garbage.”

“There’s this weird vibe that students are completing these assignments for their teachers, but this writing is for you. Don’t give your teachers the info you think they want to hear. Be the person to tell them that the quote sucks,” Baver said.

– Abby Owens

Leave a Reply