You just don’t want to learn what they’re teaching.

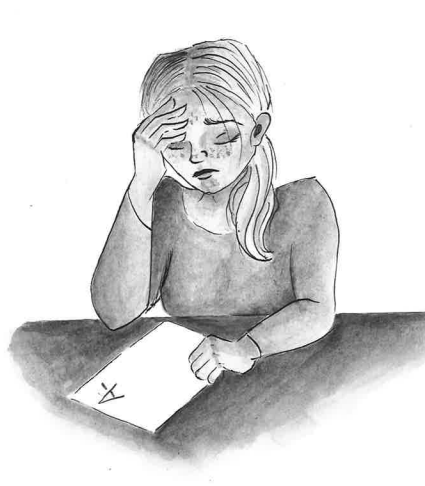

The first time I cried after receiving a grade was during my sophomore year. I could say that looking back, it wasn’t really a bad grade. But then I’d have to say what a bad grade would have been. At the time I probably had a number in mind, the divide between being content and disappointed.

I wasn’t the only one who had an imaginary number set up after hitting submit. I certainly wasn’t the only one who scored lower than this benchmark I’d made up. I also may not have been alone in saying I felt upset at the teacher during that moment. How could they not see how much I tried? Is it possible they did realize, and had still given me that score?

Was it because my view of what a fair grade would have been was completely warped?

***

The most accurate and fairest grade isn’t usually the highest one. Teenagers are so motivated by the highest value they can possibly get, no matter what they learned (or didn’t) during the class. Originally, the only goal was to make sure that people left their education system with this knowledge, regardless of what the numbers said about them.

Grades have skewed so far beyond the point of evaluation. I’ve heard people say that their grades don’t reflect what they have learned in a certain class. This is the only thing the number was ever supposed to show.

There are so many factors now, since a slim difference between percentages could reflect as so much more with a little shifting through scaling, revisions, or any other means.

The education system is advancing so much, point by point, and the evaluation system has yet to catch up with it. This gap is only growing. There’s a hunger inside most students to get the best grade they can, and we’re learning how to make sure that happens.

***

Over the past three years, I’ve had plenty of similar conversations about classes I’m taking. I didn’t notice how I became so easily swayed until recently, when I began to make my last course selections of high school.

How am I not supposed to have a mental statistic of what a good grade should be on every single assignment? It’s the defining characteristic of any word-of-mouth description of a class. More importantly, the defining characteristic of the teacher.

Oh, you’re taking that class? He’s an easy grader, I’m sure you’ll be fine.

If I get into his class, I’ll just switch sections. She’s way better at grading, anyways.

Wait don’t sign up for that class. I’ve heard she’s really harsh and your GPA could drop.

“If there’s a class that two teachers are teaching, you’ll hear ‘I want this teacher because they give better grades,’ and that’s such a degrading mentality,” said Rose Goldsmith (’25).

“One of my friends has asked ‘who do you have?’ and then would automatically get annoyed because they realized they were learning everything, but they’re not getting the grade I have. It shouldn’t even make a difference. You’re still taking the same class,” said Shreya Joglekar (’25).

If one teacher has a reputation of giving higher grades than the other, any student enrolled in that class has an immediate shift in the standard they want to uphold during the class. This standard might not be achievable and become degrading for the student, until they burn out.

This isn’t the fault of either teacher in this scenario, regardless of whether they give out the “better” grades. It’s not the fault of the student, who’s comparing themself to what they’ve been told to expect. If you’ve taken a class because you’ve been told it’s an easy GPA booster, you’d understandably feel that there was something wrong with your performance if you don’t live up to this standard.

Paul Lewis, ORHS science teacher said, “We’re fighting with those who don’t have a natural interest in your subject. with those who don’t have a natural interest in your subject. And there isn’t time to craft something to catch everybody’s attention. That’s where we have students who are listening and studying only to get a specific grade. That’s it.”

A teacher who caters to the type of student Lewis is talking about is often one considered to be a “good grader.” The teacher who knows not everyone signed up for their class because they are genuinely curious about the subject and therefore allows for minimal effort to receive a grade on the higher end of the scale.

I’m not trying to argue that a teacher who gives high grades is bad at their job. But I cannot pretend to be surprised that most students have become conditioned to feel that receiving a 100 is not only achievable, but the standard of baseline effort.

Adam Lacasse, business teacher, puts this idea into words best, which reflects the reality of his classroom. “A 100 I don’t think should be an achievable goal. It’s something to aspire to, but you might not necessarily ever be able to, and I don’t want kids to have the mindset that they know everything because of it,” he said. While he doesn’t grade students on habits of work and learning, he uses his influence to promote these ideals.

While Lacasse doesn’t want a student to have the mentality that there’s no further they can go in terms of learning, he also is known for throwing a bone to his students to help them strive successfully. “He works hard to set us up to learn… there’s practice in the homework and practice FRQ’s and he still scales the tests,” said Riley Righini (’24).

Scaling refers to the act of changing individual student grades of a test or quiz, based on the overall performance of the class. Most teachers think of scaling differently, whether it’s calculating percentages based on other test scores, or increasing by a set amount of points on all tests. In the way that Righini mentioned, scaling is used as a tool to create positive motivation for students to want to do better on Lacasse’s tests.

But in the beginning, scaling was never a variable in a grade. The grade earned was the grade received, point blank. The only motivation to perform was the fear of not doing well, and where that put you on the rank.

The idea of scaling now aims to solve that issue, so that no student feels deterred by the failure. Lewis said, “There is a positive pressure, in that we don’t want it to feel punitive and that it puts you in such a deep hole. For me, I want to make sure it’s harder for you to score in a range that’s impossible to come back from.”

While he’s working to make sure each student stays motivated inside this range, some scaling on other tests students taken can be unsatisfying. “Some teachers have said ‘everybody got this question wrong, so we’re just going to cut it out of your final grade,’ and then nobody actually learned that thing, which is the biggest problem. That’s the call to attention,” said Goldsmith.

Goldsmith is right. No teacher is objectively unfair, but some are perceived as more so when they push students to think about difficult topics. Ultimately, these are the situations in which every student has experienced a setback. As humans, we don’t grasp complicated things immediately.

This feeling of hitting a roadblock is exactly what happened to me during the sophomore year experience. I had taken classes that didn’t challenge me at all during my first year of high school, which put these unreasonably high standards and unrealistic barriers on my grades for the future.

When I received any number below this expectation, I immediately broke. Everything I thought I was capable of suddenly shattered.

It’s admittedly dramatic when someone responds to any grade below their expectations with ‘I’m going to fail high school,’ or ‘I’ll never get in to college,’ but that’s genuinely how I felt at this moment.

So, what if I went back? What if I tried really hard to figure out what went wrong, and grow from it? I knew that was an option. What’s the worth of putting in effort originally, only to need to redo it? Lacasse has struggled with offering this alternative. He said, “If I offer retakes, kids can just play for the retake, which is counterintuitive.”

Kara Sullivan, English teacher, allows for revisions to her summative assignments, but still thinks it creates disconnect between students, and their true, fair grade. “A lot of students think if they ask me to review their paper, then that means they’ll get an A,” she said.

The act of revising or doing a retake is putting more effort into the assignment, so I can understand the assumption that it will pay off. But for the student who understood the material originally and felt like they didn’t need to spend the extra time pushing themselves, now their grade might not come across with the same amount of effort, regardless of how it compares to that which was revised.

So what does a grade even reflect? Who is truly receiving a ‘fair’ grade? Are any teachers even giving fair grades?

I don’t think so. I don’t think I’ve ever received a grade that I both felt proud of and felt reflected every moment accurately, from the second I began to listen to the first lesson of a unit to the second I stood up to turn that test in.

I don’t think I’ve ever looked at my new list of classes and thought to myself ‘I’m ok with the fact that I am not in the class with the teacher that people say is a good grader.’ I don’t think I’ve ever heard someone tell me that my grades do not define me as a student, and truly believed what they were saying.

If the men at Yale University who proposed a 4.0 grading scale back in the late 1790s could read this article, would they understand that I, a 16 year old girl, don’t feel like I’ve ever received a fair grade because of their original needs to advance education evaluation?

It’s so easy for me to look back and wonder what went wrong. The only answer I can come up with is how we as students are so trapped inside the perception of what an easily achievable grade is.

For the first time in my life, I can admit that the most truly fair and accurate grade I’ve ever received was the one that made me the most uncomfortable.

– Amelia Rury

Leave a Reply