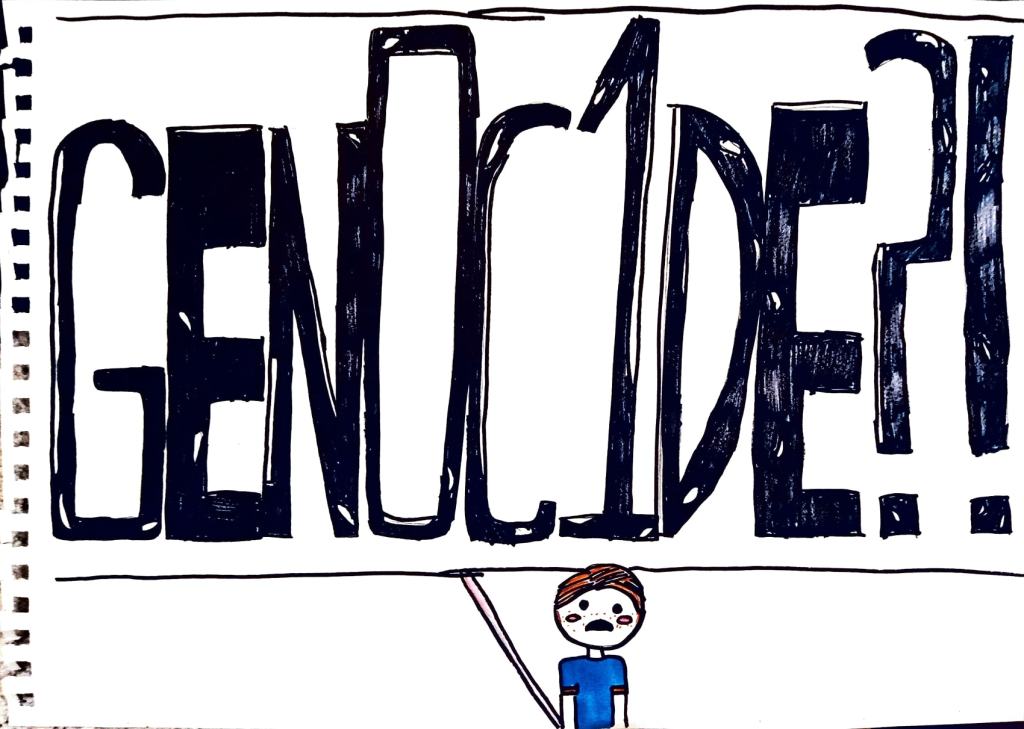

I was sitting in the counselor’s office, amid my new schedule for junior year. I was taking a long time, trying to figure out what I should fill my unwanted free period with and on a whim, I picked Genocide in the Modern World. Yikes, that’s a gruesome class title, I thought to myself.

But through taking that class, I’ve realized that the most gruesome and taboo moments in history are the ones worth learning about.

Through discussion and student-led lessons, Genocide in the Modern World makes it apparent that genocide is not a thing of the past, by opening up the conversation around it.

Whenever I bring up the class in a conversation, I swear I’ve lost count with how many weird and concerned looks I get, or the widened eyes with a frightened, Interesting… In April, the class chose to go on a field trip to the Auschwitz Exhibit in Boston and in May we taught 8th graders at Oyster River Middle School about genocide and the different topics surrounding it. Each time I told people around me about these events, their face automatically drops.

Which, in their defense, genocide isn’t really something that everyone just brings up in a normal conversation. But with the multiple humanitarian conflicts that are happening in the world as we speak, it should at least be considered as something to process, maybe out loud.

Genocide isn’t something that happened in the last century, it can happen now.

Miles Gans (‘24) a student in my class, has observed that the more time we spend in this class, talking about genocide, the less taboo it becomes. He states, “Because it’s dealt with sensitivity and all of us are so used to talking about it, it’s just another topic we’re talking about, rather than it being something people would rather not touch on at all.”

Having this opportunity to be able to talk to other people about genocide in a way that can be done freely, but not being insensitive is what makes Genocide in the Modern World stand out. I remember in past history classes, when we would go over the Holocaust unit, our teacher would try to start a discussion, but either nobody would be comfortable talking because of the seriousness of the topic, or people would treat it as a joke.

Lily Pappajohn (‘26), another student in the class, thinks that the people in the class, really drives the class to its core. She says, “Everybody’s taking it seriously, which really helps…we want to learn about the topic, we wouldn’t have taken the class otherwise. So sometimes, it is hard to talk about it, but we’re still able to learn from each other.”

A way to learn from each other can be through making the curriculum of the class student-led. Gabrielle Anderson, a social studies teacher at Oyster River High School (ORHS) and the teacher of Genocide in the Modern World made this class be more seminar-focused and student led to better push her students.

She says, “I had a vision of what I wanted [the class] to be. And then you have the students, and that vision often changes for the better.” Along with informing her students about genocide, she makes sure that they are as equally interested in the lesson plan as she is.

Gans has seen himself become a better and more involved student in the class because of the focus on student involvement. “It’s more student focused and more what people actually want as a collective than what the teacher wants to teach us, I think that’s valuable.”

In our class, making our curriculum student-led means that students have more space to explore what we want to learn with input from our teacher. As an example, when we first started learning about the Cambodian genocide, we first learned the very basics; the who, the what, and the when. But for our project, we branched off into answering a question out of the 10 or so questions that the class came up with.

That way, we made lessons so that each question on that board was answered and cover all curiosities about the genocide, because most of us haven’t heard that much about the Cambodian genocide.

Learning about genocides and humanitarian conflicts that weren’t the most covered back then or even now makes us better aware of the world around us. Those people that passed away because of mass killings, who were taken away from their families, from who they were before, still deserve to be remembered just as much as Holocaust victims.

Anderson realizes this and tries to get students to learn about how these acts can take place in the modern world. “It’s really important for students to learn about [genocide], especially with…still a lot of modern stuff that’s happening that students may not know about. Understanding the patterns behind genocide and the why’s can point to how it can be prevented.”

Although a class can’t singlehandedly prevent a genocide or humanitarian crisis, we have already prevented one thing: silence.

Because after all, silence was what caused these genocides to be a part of our history books in the first place.

– Hannah Klarov

Leave a Reply