It is a frigid Monday morning in October, and the cold seeps through the walls as I roll out of bed. The blaring alarm breaks my sleep—it’s six a.m. I stumble to the clock, hit the switch, and crawl back under the covers, desperate for more rest.

Teenagers need eight to ten hours of sleep per night according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But despite this statistic, many Oyster River High School (ORHS) students find themselves consistently with excessive homework, making those eight hours feel impossible.

Last night, I got six hours. The night before? Maybe seven. Today? Six again. At the time of writing this article, my mind burns from exhaustion, my eyes waver shut, and I’m not alone.

For most ORHS students, eight hours of sleep means going to bed at ten and waking up around six. But there simply is not enough time in the day to be in school for seven to nine hours and still manage homework, extracurriculars, work, and family responsibilities, while continuing to designate time to decompress and socialize. Sleep is often the last priority for most students, who are often forced to sacrifice sleep for success.

This is not an issue of time management. This is an issue of ORHS overworking students.

I contacted Yury Ovchinnikov (’25), one of the busiest seniors I know. I wanted to know his thoughts on this issue. So, we set up an interview over the phone. When I asked him how much sleep he regularly gets, he said four hours.

This is not healthy.

I was wondering what the most detrimental effects of sleep deprivation were, so I sat down with ORHS Nurse Kim Wolfe. She told me that when you are sleep deprived “your concentration is off, you’re not going to be as mindful, you’re not going to be paying attention like you should… [and you’ll be] thinking ‘I can’t wait to get home to sleep’ instead of thinking about the calculus or whatever is in front of you.”

Wolfe’s explanation perfectly summed up how I feel every time I am sleep deprived. Recently I have found this unavoidable feeling sucking the enjoyment out of my usual positive experience at ORHS.

It is a negative cycle too. I remember during my earlier years of high school I would nap after I got home. The naps I used to compensate for my sleep deprivation could span up to two hours. This made me stay up even later into the night, as I wasn’t tired anymore after that rejuvenation, and the cycle continued.

Harrison Burnham (’25) doesn’t share Ovchinnikov’s opinion. “I choose when I go to sleep, I choose to watch football until eleven-thirty at night, and I [also] choose to work until eleven at night, so it’s all in my control,” he says.

However, contrary to Burnham’s point, teenagers’ circadian rhythms push sleep back later into the night according to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF). Because of this, their attentiveness is delayed until later in the day. So, yes, technically it is the choice of the individual as Burnham points out, but the freedom in that choice is limited.

Every time I discuss sleep deprivation with people, I hear the descriptions of similar causes: social media, the usage of technology immediately before bedtime, poor time management, and procrastination. But none of these ideas really circle back to the root of the problem.

You might be wondering: Why is sleep deprivation such a pressing issue now? It comes directly from students consistently working hard and juggling more than ever to succeed, with the schedule serving as a limitation.

Since social media algorithms utilize our inherent human vulnerabilities for profit, we are helpless. So, using the argument of high screen time among teens to explain why they don’t get enough sleep feels convoluted. This is not an issue we can solve. But we can change how we create the schedule to better serve ORHS students.

“I think having classes every other day is beneficial [compared to seven classes a day]. That said, why stop there? Why not keep looking into different ideas for alternatives?” says ORHS social studies teacher Derek Cangello who believes “We have basically the same schedule that we’ve had since 1950.”

You might be thinking we solved this issue when we changed the start time from seven to eight a.m. in the last decade. But when I asked Ovchinnikov if he thought less time in school per day would resolve this issue, he said “I don’t think [shortening the school day] will change anything, because if the teachers have less time to teach during school hours, then they will just assign more homework.” The issue of overworking still persists. “[I think teachers need to] be more mindful of how much time [homework] should take,” he adds.

As a solution, Ovchinnikov proposes a calendar idea, where teachers could see how much work students manage each day, making them more mindful of students’ time. The calendar would likely be visible alongside Schoology, to make it easier for teachers to see how many commitments students are managing beyond each respective class.

Some argue that homework in high school is meant to foster student exploration. However, it is important to remember that students are typically willing to explore on their own, outside of the confines of school.

Students’ time is already scarce, yet social media companies continue to monetize it. And we can’t escape. Think of all the times you were bored and picked up your phone to text a friend. Those weren’t impulses we could control. We need to work with the variables we can control, like the schedule itself.

On the topic of the schedule, Cangello says, “We need to think outside the box.” He explains how during COVID, students had Wednesdays off school. This change allowed them to devote time and energy to schoolwork during the school day and prevented day-to-day activities from interfering with their sleep schedules.

I’m not saying we need more remote learning. But we do need to find a way to incorporate more unstructured time into our days, more time for what is important to each individual student. We can’t operate ORHS with a one-size-fits-all approach. It’s detrimental to those working diligently, tirelessly, and around the clock to succeed.

“The natural place to steal time is from your own sleep,” says ORHS philosophy teacher Eden Suoth. But what are we truly stealing from?

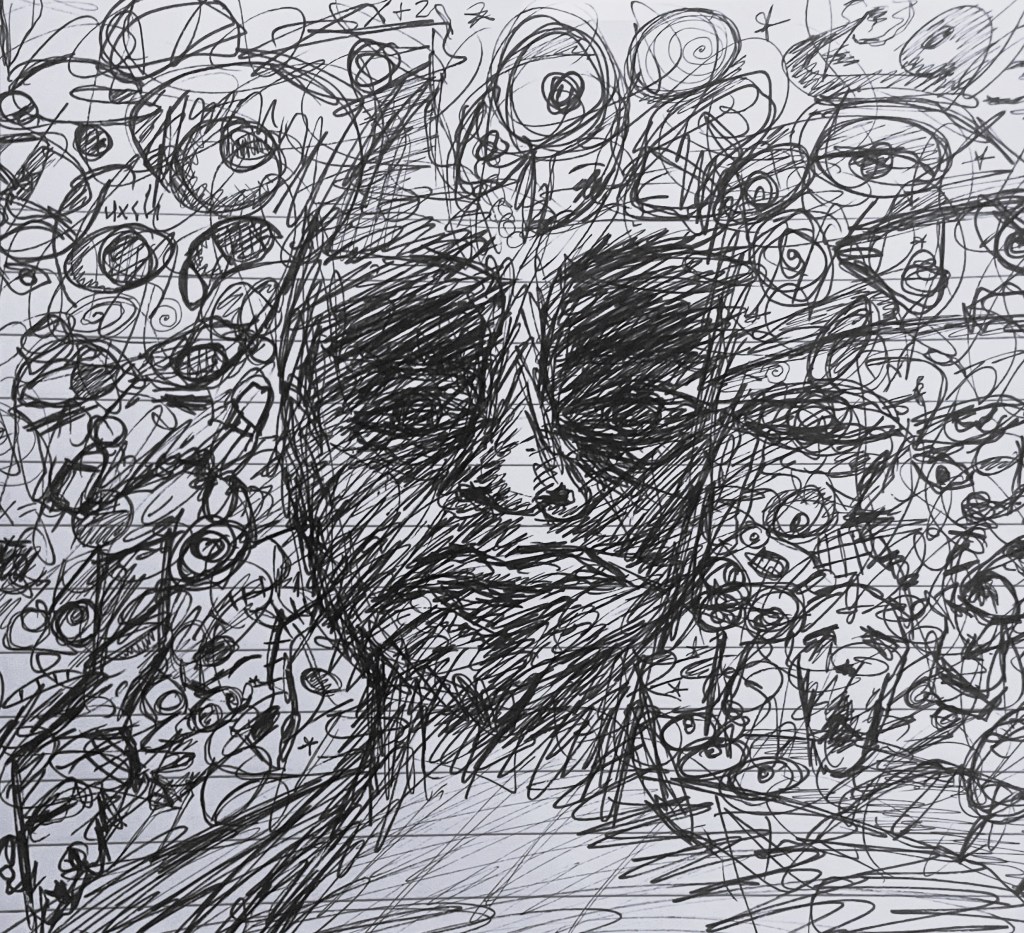

This is Givanni Macisso’s (’25) artistic interpretation of sleep deprivation.

—Ulysses Smith MOR

Leave a Reply