What’s the hardest word for you to say?” my new speech-language-pathologist (SLP) asks me. We’re walking down the clinic hallway, and my eight-year-old self knows exactly what my answer is.

“Woh-wah,” I tell her. Both her and my mom scrunch their eyebrows together.

“War?” the SLP asks.

“No, woh-wah. Like the Katy Pewwy song. Or a tigah,” I say, impatient.

Double Rs. The bane of my third-grade existence. Like many children, I struggled with what are called articulation errors—being unable to produce a certain sound. My mom was constantly irritated with my lack of pronunciation. I didn’t know what she was talking about: “It’s just my accent, Mama!” I would claim.

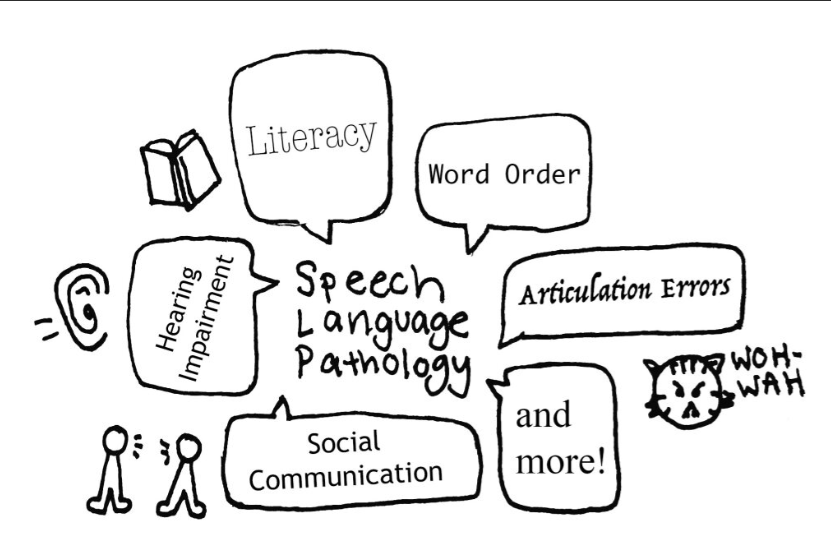

I went to Moharimet Elementary School in Madbury, NH, and my mom asked the school if I could receive speech therapy. Otherwise known as speech-language pathology, this is a field that works with people of all ages to communicate better, including topics such as social speech, articulation errors–like those Rs I struggled with–language processing, and more. Unfortunately, I didn’t qualify for this program, so instead I went to a private practice—getting the same help I would have gotten at the school level, just more expensive.

Neither my mom nor I understood why I couldn’t get speech therapy through my school. Wasn’t that their job? To fix the speech sounds of R-less little girls?

Ten years later, I decided that I wanted to be a speech-language pathologist. As I interned and observed at different SLP practices in Dover and Durham, NH, I noticed that they worked with so many things, such as selective mutism, social communication, and word-order. When I talked to the speech pathologists of the Oyster River Cooperative School District (ORCSD), they all told me what I had found through observation: We work with so much more than speech sounds.

The misconception, of which I am guilty of believing, that SLPs only work to improve the Rs of eight-year-olds, makes it so the program is pushed to the sidelines, as if what SLPs do isn’t as important. I sought to dive in deeper into what they do, and why they do what they do. They answered my questions, and hopefully, they will answer yours.

1. Why become a Speech Language Pathologist?

Juliann Woodbury knew she wanted to be a speech pathologist thanks to a waiter with the body of a Greek god.

When she was fifteen, she worked her first job as a busgirl at a fancy restaurant in Exeter. As she worked, she quickly took notice of a waiter in his early twenties who she found exceptionally attractive—she described him as a “Greek god.”

The Greek god was part of the “back staff,” the employees that worked on cooking and delivery and weren’t designated the “face” of the restaurant. Woodbury didn’t understand— why would a man who looked like that be hidden in the back?

One quiet night, a few months into her job, she learned why.

As the Greek god was serving a table of 12, Woodbury eavesdropped and was startled when she heard something unexpected. Her coworker, seemingly the perfect poster-child for the face of this high-end Exeter restaurant, had a stutter.

He got stuck in the “N” of one of the words he was trying to say, and it seemed like it went on forever. Woodbury continued to clear the table–she didn’t even know what stuttering was and just looked around helplessly.

The next day, Greek God came over to her, and said, “I assume you probably have some questions.”

Woodbury says, “I remember like on those slow nights, I just started picking his brain…he admitted he said he went through a lot of speech therapy…I think within about two or three days of that event, I decided what I wanted to be. And I never wavered.”

Those nights led Woodbury to eventually work at Oyster River Middle School (ORMS) as their SLP for going on 23 years.

The idea that speech-language pathology works with articulation and speech sounds is not a far-fetched concept, because a lisp is what got Woodbury into the field. An R-sound is what got me into the field. However, sometimes the love of speech-language-pathology comes from a group of Deaf individuals in a music store, without any speech sounds at all to be heard.

Amy Leone, Mast Way’s SLP, was an aspiring journalist as a teenager and loved to write. When she wasn’t pursuing that passion, she had a high-school job at a music store nearby.

One night, a group of four Deaf individuals came into the store with their case manager: and they were looking for music.

Leone was young, and very confused. The case manager, sensing her confusion, told her: “They love the feel of classical music.”

She learned that these Deaf people could feel music through tactile means, which blew her mind. That first night, teenage Leone went home and started looking through the course catalogues being sent to her, as she was a senior, about to graduate. She thought, I really want to help people who can’t communicate.

“It stuck in my brain…for me that I wanted to help people who couldn’t communicate. That interaction with that group really did something to me. So, after that, I found a description for [the major of] communication disorders, and the rest of my life is history,” says Leone.

Years later, Leone, Woodbury, and the rest of the ORCSD’s speech pathologists find themselves working with many different disciplines in the field: including and beyond articulation/speech sounds.

2. What does a Speech Language Pathologist do then, if not just speech sounds?

Victoria Sandmaier, another one of ORMS’s SLPs (with a focus on grades 5/6), says “There’s always a little petition that goes around certain times of the year…where people want to change the name of our profession.” Because, while speech is in that title, the job is so much more than that.

“So with speech therapy, what most people think of is just sounds, and that’s a decent amount of kids that I see. But then there’s children who have difficulty expressing themselves, or vocabulary, putting sentences together, telling stories, understanding language, following directions, children who are on the autism spectrum, so social language, or hearing impairment,” says Rebecca Anderson, Moharimet Elementary School’s SLP.

“The teacher has to really say to me, ‘I don’t understand what they’re saying.’ Or ‘they won’t talk because other kids don’t understand them, so it’s interfering with their classroom communication.’ Another reason could be when they’re writing, they’re writing the way that they’re talking,” she continues.

This explains why I, at eight years old, didn’t qualify for school speech therapy: people could understand me just fine. Anderson referred to the type of speech impediment I had as “cosmetic,” saying, “That is not a disability. It’s just a little bit of a difference.”

Part of the misconception that SLPs only work with speech sounds have people questioning why an SLP is employed at a high school. After all, teenagers have probably moved past the point of speech impediments, right?

“Almost none of what I do here is articulation anymore,” says Emily Johnson, Oyster River High School’s SLP. She discussed the most common topics she addresses in her work, such as expressive and receptive language, social communication, and working with language and literacy.

Speech pathologists cover everything from articulation errors and lisps, to reading, decoding, comprehension, and writing. “I think that the reach and the impact of speech and language pathologists can have, especially in a public-school setting, is far and wide and deep… I think we have a lot to offer to any educational team,” says Leone.

3. What’s it like to be an SLP in a school?

At this point, I knew the extent of the range of topics SLPs work with. However, through my time observing at private and clinical practices, I’d wondered what was different about working as an SLP in a school setting.

“I think public schools have so many benefits for students and being able to see them grow in all kinds of ways, social, academic, speech and language, I think that’s a huge benefit for me,” says Leone. “I’ll meet my students in kindergarten…. watching them grow from a five-year-old into a student ready to transition into middle school…the growth that I get to see: them developing into young humans and getting ready to go to middle school is really powerful and motivating to keep going.”

The concept of growth is a common theme for school SLPs and is seen in the middle school environment as well. “You’re literally watching kids from fifth grade to eighth grade transform from being very concrete to being able to do some abstract thinking. And it’s fascinating, and that’s one of the things I love because you’re watching the transformation,” says Woodbury.

Throughout the grade levels, how an SLP works with a student varies. Amber Goolbis works with 3–5 year-olds in the Preschool Education Program (PEP), the youngest age group in the ORCSD. The program consists of 50% “typical” children, and 50% children with identified speech/language and/or occupational therapy needs. All the children, though, are pretty much the same in many regards: for one, “They’re adorable. Have you seen them?” says Goolbis.

However, for preschoolers, it’s hard to only be able to focus on speech and communication with them. Goolbis says, “They’re not just learning their communication skills, they’re learning bigger life things like self-regulation and that can be hard. There’s not a lot of reasoning with a three-year-old who’s in the kind of meltdown state, although that could be said for some older people as well.”

This is found to be true a lot with the SLPs who work with younger ages: for Anderson, working with elementary schoolers, “Sometimes you feel like you’re spending most of the time corralling them as opposed to getting the work done.”

Luckily, in a one-on-one setting in a high school, less corralling and more teaching can be done. Johnson had gone to ORHS as a student, and after working with adults with traumatic brain injuries in the rehab setting, decided she wanted to work with kids again. When she started her job at the high school, she says, “I took the position, hoping to eventually move to younger grades. And then I ended up really liking it, because… there’s a huge variety in what I get to work on in a day, which is fun and keeps it interesting,” she says.

Not only does working in a school benefit the SLPs, but the work they do with these students is immen sely impactful—which brings us to the final question.

4. Why is speech pathology in schools important?

When I set out to write an article on a profession that I’m so interested in, I worried no one else would understand why it means so much. How do I tell people that this aspect of ORCSD and districts across the country is so very important? Luckly, the SLPs I interviewed said it better than I ever could.

“What’s at the root of all our lives? Human interaction and communication,” says Goolbis. Starting young, starting in schools, when language is still developing and somewhat moldable, is important for struggling children to become successful adults.

Without understanding one another through communication through language, we would have no society, and no community. Woodbury says, “You have a strong community when you have good communication. It’s sort of the glue. Like, the community takes all the pieces and parts and the people–what makes it function and what makes it healthy is communication.”

Thanks to the speech-language pathologists of the ORCSD, the children in our community can communicate—whether it’s word order, social communication, a lisp, or saying our Rs.

–

-Paige Stehle

Leave a Reply