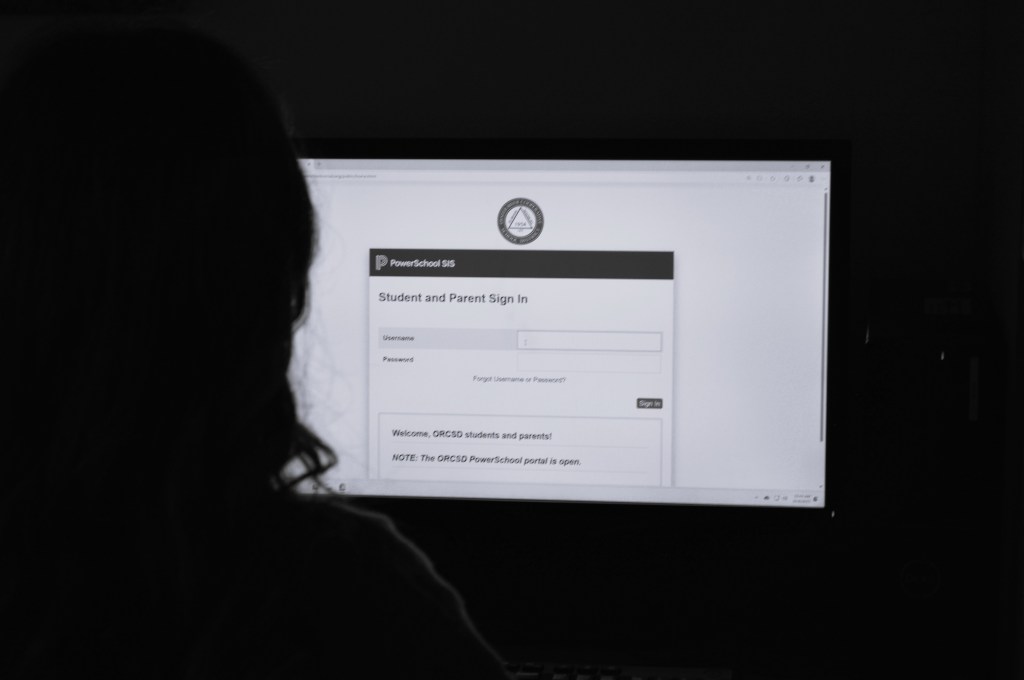

Bzzzzz. I glance down at my phone laying face up on the table. A notification illuminates the screen. “Your grade has been updated.” I immediately grab it and with shaking hands, navigate to PowerSchool.

PowerSchool is a student information system (SIS) that is used by thousands of K-12 schools across the country including Oyster River High School (ORHS). In addition to being in constant use on school laptops, the app versions of PowerSchool websites also allow students to be constantly connected even outside of school, receiving notifications alerting them of every grade change, often by as little as a single point.

I consider myself to be a very academically motivated person. I like feeling in control of my education. I like knowing how I’m doing in my classes. However, throughout my high school experience, I’ve noticed that having 24/7 access to my grades often causes more harm than good. As an underclassman, I would check my grades every spare moment I had. In class. In advisory. In my free time. Even now, I constantly pick up my phone mid conversation just to check PowerSchool notifications. While staying on top of grades and schoolwork is highly encouraged and essential for success as a student, there is a point at which obsessing over every grade change becomes wildly unhealthy.

Even with the recent implementation of the statewide law banning phones in schools, I find myself consistently checking my grades on my computer instead. Lucky Muppala (‘26) has found herself in a similar boat. “If I have my laptop out, I will literally go on it every single class at least, just to see if there’s anything uploaded,” she says.

An opinion piece from The Daily Northwestern titled “The Grade Obsession Trap”, dives into how grade obsession in general, is a barrier to learning and can ultimately hinder one’s educational experience. Phrases like “don’t take that class it’ll drop your GPA,” or “we don’t have to do that assignment, it’s not graded” are constantly thrown around. This article talks about how “A-level students” aren’t necessarily getting the most out of a class or lesson, only doing whatever it takes to get a perfect grade.

Paul Lewis, a science teacher at ORHS, shares that he’s noticed this pattern among his students and advisees. “[For] some of them, every time in flex, every single day if their laptop was out or their phone was out, they were checking their grade, which feels like focusing on the number more so than the actual learning that’s going to their future,” he says.

Lewis’s teaching philosophy is based on fostering student’s knowledge and understanding in a way that will benefit them in the long run, beyond their high school transcript. He says, “what really matters in the grand scheme of the thing is what skills and things you’re learning here that are going to impact your future later on, where nobody’s going to remember your grade from high school.”

However, while Lewis focuses on developing skills in the classroom that will stick with students even after the big tests, he recognizes the desire and necessity for maintaining good grades. We as students are stuck in a system where our GPA determines our worth. Not only to ourselves, but to colleges and universities as well. It’s the first thing schools look at to filter out “incompetent” students. The first thing that can get you rejected without the rest of your application even being considered. Advanced high school classes, which are supposed to prepare us for the “real world” and success at post-secondary educational institutions are simply digital boxes on our transcripts to be filled with A’s by whatever means necessary.

Because of this, for many, what’s taken out of a class isn’t nearly as important as what’s put in PowerSchool. Knowledge, meant to prepare students for the next level, is no use if grades limit them from getting there in the first place.

Lewis recognizes this and implements strategies in his classroom that allow students to excel in the understanding of a subject and have grades that accurately reflect their effort and knowledge. From allowing retakes in his lower level (non-AP) classes, and offering grades up to full credit, his approach to teaching is allowing his students to become less obsessed with the number in the gradebook, and more obsessed with learning. Lewis says, “I want to make sure students have the ability to achieve highly so that they can go to the next step of their life after high school and have a chance to be competitive with students in other districts.”

However, this issue extends far beyond any single teacher. I’ve found that the toxic cycle of tying my entire self-worth to numbers, a result of my strict grade checking regimen I’ve withheld throughout the entirety of high school, seems to follow me even outside of college applications.

I am fortunate enough to say I know what I’m doing after graduation. I’m committed to college. A few points on PowerSchool shouldn’t be all that important anymore, yet I still can’t seem to shake this addiction. I still find myself cramming for tests, frantically writing in the middle of the night, not because I’m passionate about my classes, but because I can’t stand the thought of not getting perfect grades.

“Grade obsession and why it’s a serious problem”, an op-ed from Penn State, describes high school as a “regurgitation society.” This refers to the cyclical act of teachers piling their students’ plates with information and resources only for them to spit it right back up on tests, soon to be shoved to the back of the mind along with dozens of other hastily memorized formulas and late-night study sessions. In the end, students never end up truly understanding the material.

This article highlights that along with hindering students’ creativity in the classroom, intense obsession with numerical performance can cause serious mental implications, including high levels of anxiety and self-doubt along with other severe mental health issues.

I recently spoke with Jaclyn Jensen, a psychology teacher at ORHS, and she introduced me to the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Like its name, intrinsic motivation is internal. In terms of academics, it refers to students who are motivated from within; who put effort into their schoolwork because they have a passion for learning. In contrast, extrinsically motivated students — those who work hard for external validation — are more likely to become grade obsessed and develop a PowerSchool/grade checking “addiction”.

Jensen also shares how this mindset can not only lead to high anxiety in students but can also contribute to poor mental health that follows them well into adulthood. “You spend your entire academic career really focused on getting the validation from the external source, from the grades, from your teachers, from your professors, from advisors, and then one day none of those factors are part of your life anymore,” says Jensen. Former grade-obsessed students may struggle to find motivation from themselves once academic validation is no longer part of the picture.

It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that grades aren’t the end all, be all. However, once we start treating our classes as what they truly are — an experience, not just an evaluation — we begin to not only develop a healthier approach to grades but see more success as well. “Kids don’t realize it, but by being purely motivated by getting the highest number as possible, they produce work that [doesn’t get] as high a grade as it would if they focused on the learning process… you actually end up producing better work and getting higher grades than when you’re [not] just concerned about the outcome,” says Jensen.

As Jensen highlights, obsession in itself can be an inhibitor for success. While like it or not, PowerSchool isn’t going anywhere, for the first time in my high school career, I can say that my phone no longer lights up every time my grade changes.

-Jahrie Houle

Leave a Reply